Of this philosophical wonder it should be observed, because it bears on our ground of belief, that its tendency is not, like that of ordinary wonder, to diminish through familiarity, but rather the reverse. Awakened by the fact of being, necessarily involving the idea of being uncreated; also by the discovery of the immensity, and order, and movements, and adaptations of that around us which we call the cosmos, it increases as its object is dwelt upon till it becomes utter bewilderment. Whoever, therefore, recognizes all this, and accepts it as a reality, ought to have no difficulty on account of its strangeness merely, in accepting any form of the manifestation of being that may claim his acceptance. That there should be a future life under a different form cannot be more strange than that there should be a present life under its present form. That there should be a heaven hereafter cannot be more strange than that there should be a happy family here. That there should be a spiritual existence cannot be stranger than that there is a material existence. That there should be a personal God, infinite and holy, cannot be more strange than that we should be personal beings, as we are, and that there should be this multiform universe in which we find ourselves. Indeed I think we may say, that live as long as we may during the eternal ages, go where we may into the depths of infinite space, we shall never find a scene of things more strange and wonderful than we are in now.

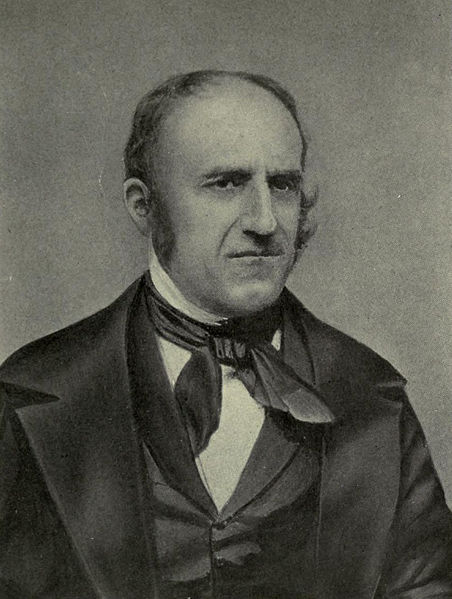

From Mark Hopkins’ The Scriptural Idea of Man. Hopkins was a legendary teacher (he taught at Williams in the middle of the 19th century). Bliss Perry, in his winsome book, And Gladly Teach, talks of Hopkins’ power as a teacher.

No one can furnish an adequate definition of greatness, but Mark Hopkins, like Gladstone and Bismark, gave the beholder the instant impression of being in the presence of a great man. He had already become in his lifetime a legend, a symbol of teaching power: ‘Mark Hopkins on one end of a log, and a student on the other.’ [This line originated in a comment of James Garfield’s (one of Hopkins’ students): ‘A pine bench with Mark Hopkins at one end of it and me at the other is a good enough college for me.’–KDJ]

[His students] all agree that he was not, in the strict academic sense, a ‘scholar’; the source of his power was not in his knowledge of books. But that is an old story in the history of the world: ‘He taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes.’ Any teacher can study books, but books do not necessarily bring wisdom, nor that human insight essential to consummate teaching skill…

To some men in class, no doubt, he seemed a philosopher without a system, a moralist indifferent to definitions. He was in truth a builder of character who could lay a stone wall without ever looking at a blue-print.

All of us recognized his immense latent power. ‘Half his strength he put not forth.’ Yet this apparently indolent wrestler with ideas–never dogmatic, never over-earnest, never seeming to desire converts to any creed or platform–was ceaselessly active in studying the members of each class and in directing, however subtly, the questions by which he sought to develop and test their individual capacity…