To get the final lilt of songs,

To penetrate the inmost lore of poets–to know the mighty ones,

Job, Homer, Eschylus, Dante, Shakspere, Tennyson, Emerson;

To diagnose the shifting-delicate tints of love and pride and doubt–to truly understand,

To encompass these, the last keen faculty and entrance-price,

Old age, and what it brings from all its past experiences.

Category Archives: poetry

Ears to Hear: Bill Mallonee’s *Slow Trauma* (Music Review Essay)

I

Earlier this week, I was walking across the red brick and green tree campus of Auburn University, where I am lucky enough to teach philosophy. My daughter–a rising senior philosophy major–was walking with me. We were chatting, and, our chat, as our chats often do, turned to books. My daughter reported that she was nearly finished with Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead.

As my daughter knows, I venerate Robinson. If Robinson were to walk toward me on the sidewalk, I would step off, doff my cap, and cry, “Empress!” as she passed. I deeply admire Gilead. My daughter continued: “But I think I am going to have to read it again when I am older. I don’t think someone my age can fully understand that novel.” I stopped and thought for a moment–then I agreed. “Yes. Some novels you can understand because you can make do with your imagination to fill in where necessary. But with other novels, only experience can fill in where necessary. You can imagine being experienced; but that will not substitute for experience where it is necessary. James Gould Cozzens’ Morning, Noon and Night is another novel like that. You have to have lived forty years or more fully to understand it.”

II

I recall this conversation because it highlights an important fact about Bill Mallonee’s fine new album, Slow Trauma. This album, which I think continues what is now a conceptual trilogy of albums that includes Winnowing and Lands and Peoples, is perhaps the Mallonee album that is most clearly the result of his long experience and experiment in art and in living.

The slow trauma is life itself. We know–late at night, when we cannot sleep, and the ceiling reveals nothing, and our joints cry bitterly about their long misuse–cringingly, we know at such moments that no one escapes life untraumatized. But we forget that the trauma has been on-going since our first greedy suck of breath, accumulating. We keep such thoughts at bay when we are young, maybe we do even until we get just past halfway betwixt mother and Maker. But eventually, they settle on us, heavy: we are at war with Time: we are going to lose. Time is a bloody tyrant. He happily besieges us. He can wait for the walls to fall. Beginnings and endings are his speciality. But he is done with our beginnings. Our endings are all that are left.

III

Mallonee’s album is neither a carping lament nor a willful carpe deim. Its dominant tone is reverence. Mallonee has a deep understanding of human limits–and of the human limits in handling human limits. He knows we would like nothing more than to deny our humanity and to transcend those limits. We so imagine them that we run against them, believe ourselves to be caged by them. But there is no cage. We are limited to our nature but not by our nature. Our slow trauma is our slow trauma.

Mallonee realizes that coping with our slow trauma necessitates acknowledging it as part of who and what we are. It would be nice to opt out or be lifted up, be caught up in a cloud or be given a spot on some low-swinging, sweet chariot. But neither is likely to happen. We have to hoe our row to its end, sweaty and dirty, knowing the weeds grow back when we finish. But while we hoe, we are surrounded by mysteries. Our hoeing, our living, has a meaning–but that meaning has not been vouchsafed to us. And what would it matter if it were? How could we recognize it as the meaning of our life? And how could what I recognize be the meaning of my life, if that recognition comes before my final chary exhalation? My life after I have recognized the meaning of my life would then not be able to change the meaning of my life. But that cannot be right. Repentance, at least, is always possible, even if it is unlikely.

We are homo viator. We are in passage, in transit. The meaning of our life is not available to be known until we are not around to know it–and maybe not even then. The meaning of our life extends past our death into the lives of those we have touched and those we have refused to touch. Our journey’s end is our end, our last stop our last stop–but our meaning travels on. It continues without us. We don’t arrive, and then get to go and see the sights. Arrival at our destination is our departure for Parts Unknown.

We have to live within these limits. –How do we do that? Mallonee opens the album with a short song (“One and the Same”) responsive to the question.

What to hold onto?

What to let go of?

And what to give away?

What’s going to save you?

And what makes you smile?

Sometimes, they are one and the same.

We often see things under aspects. The thing I need to keep and the thing I need to reject are sometimes the same thing–but seen under two different aspects.[1] What exalts me is the same thing as what makes me chuckle–but under different aspects. We deplore this state of things. We want to be able to see under nothing, non-aspectually. But when we try to see what is both needful and rejectable, but to see it non-aspectually, it simply recedes into some indeterminate, more or less middle distance, neither foreground nor background, just an irregular clump amidst visual clutter. This means that we cannot have what we want, some final, non-aspectual vision of the thing. We are stuck with it as both needful and rejectable. This is not a problem to be solved, but a condition of our lives. Things don’t sort for us. They remain a weird tangle, knotted to us and to each other inextricably, in inexplicable ways. No final preference ordering is forthcoming.

IV

We are curious about Parts Unknown. We wonder at mysteries. As we should. Still, we need to remember that mysteries are not unsearchable because they are abysmal, dark rifts. They are unsearchable because they are blinding, consuming fires. Those fires create the light in which we see light. We live in the light of mysteries, surrounded by uncreated light. We come to understand the mysteries, to the extent that we can be said to do so, not by staring directly into them, as if we could interrogate them, but by looking ever more carefully at what they allow us to see: the world around us, and especially other people. We understand the mysteries by caring for what they show us. (We love God by loving what God loves. Thus are the first and second commands forever yoked together.) Our spiritual posture toward the mysteries is forever interrogative–but our question-marks are not symbols of skepticism, but of a desire to progress from glory to glory, to move ever deeper into the Heart of Wonder. The next of the wine in Cana is better always than the last.

You know, it’s funny how things can get so damn misplaced

Where you bet your farm and where you place your faith

And time is such a precious thing to kill

I just wanna see over that last hill

Will my highbeams flood the plain?

Will the Gatekeeper know my name?

Will there be Someone to claim me for his own?

Well, you whisper to yourself when time runs low

Darling, I’ll carry ever smile we shared with me when I go

Lord, gather me unto Thyself when my wayward heart grows still

I just wanna see over that last hill (“That Last Hill”)

It is important to recognize that this is an entreaty, a prayer, not a demand. Mallonee asks to see. Mallonee’s aversion is the clenched fist, the demand aimed at heaven or at earth, the refusal to touch unless it is to hurt–but he also knows how easy it is to clench the fist, to treat the mess, the ugliness, the pain, the worry, as excusing the fist: it is easy to harden our hearts and curl our fingers. Reverence sours into resentment. The light of the mysteries fails us–because we fail it–and so the light we see by is now itself unlit. The world becomes a grey-on-grey assembly of petty nothings. We all know the temptation of such moods.

No, it’s not really a good time. No, it rarely is these days.

Loneliness she washes over you like a wave;

And the snow is ever falling down.

Doldrums in Denver…Doldrums in Denver

And it’s time you leave this town…There ain’t nothing for you now.

(“Doldrums in Denver”)

In such moods, faith and hope seem hellish currency, too awful to carry. We cannot keep ourselves from such moods. They come and they go, and fighting against them when they come tends only to aggravate them. To blacken their shades of grey. All we can do is let them come, endure them (yes, even, after a fashion, reverencing them), in holy indifference, asking for nothing and refusing nothing. One of Mallonee’s greatest strengths as a songwriter is his gift for writing from and creating in his listener this holy indifference. (The ‘holy’ here is an alienating adjective of a complicated sort; it changes the register in which we should hear ‘indifference’, making of indifference a yielding, a pliancy, an availability, instead of self-willed stoicism.) Such a state is, I hazard, Mallonee’s most fecund state as an artist: his best songs seem to me to come from a state of waiting. And, as a result, they re-create that state when–perhaps even most successfully when–the songs are not in any way about that state. As Emerson once said: “Character teaches above our wills.”

V

Holy indifference and reverence are not two distinct states. They are rather the inward-looking and the outward-looking faces of the same state. It is a state opposed to the state expertly captured by Alan Dugan, in “Passing Through the Banford Tolls”:

Proceeding sideways by inattention I arrive

Unknowingly at an unsought destination

And pass by it wondering: what next?

This is not the sort of wonder Mallonee seeks to cultivate, the inanition of boredom. Mallonee’s waiting is of a qualitatively different kind.

VI

The most remarkable song on Slow Trauma is “Waiting for the Stone to be Rolled Away”. It opens with a lilting, meditative guitars, anticipating the melody. It then settles into a gentle, upbuilding cadence. The first verses and the last:

There’s a halogen glow cast from across the street

From the parking lot of the Holy Spirit Assembly

It’s a beacon in the desert night until the break of day

Waiting for the stone to be rolled away

I told Solomon, the shepherd of the flock

I’ve got none of the gifts he’s got

You see, you cannot speak in tongues if you’ve got nothing to say

Waiting for the stone to be rolled away

….

Baby, gimme those keys, sit back and just watch me

Navigate this thing back home with considerable ease

Down these sad, back streets of doubt to a new and brighter day

Waiting for the stone to be rolled away

This song manages three levels at once. One, the actual scene in the desert night; two, Mallonee’s reflections on his own work as an artist; and, three, a metaphysical representation of the human plight. (Consider the density of the name, ‘Solomon’ here–the name perhaps of the actual minister of the Assembly, the name of the writer of the Songs, the name of the not-entirely-grateful vessel of God’s wisdom: “I have seen all the works that are done under the sun; and, behold, all is vanity and vexation”. –Doldrums in Jerusalem.) Mallonee’s gift of tongues, perhaps not a form of Pauline glossologia, but a gift nonetheless, is real. But he too needs an interpreter, someone with ears to hear–someone who has not only had experience, but lives and has lived in devotion to that experience, intent on creating a heart that passes out of itself. We are all waiting for the stone to be rolled away.

VII

This brings me back to my wise daughter, and to Marilynne Robinson. Some things we grow into understanding. We have to develop certain habits of mind and feeling, and that takes time. We have to learn how to hear–we need the proper acquist of experience, and we need training in how to listen, lest, hearing, we not hear. We have to become human ourselves in order to hear the music of the human voice–in order to understand. Robinson, contemplating this issue in her essay, “Wondrous Love”, writes:

Jesus spoke as a man, in a human voice. And a human voice has a music that gives words their meanings. In that old hymn [“In the Garden”]…as in the Gospel, Mary [Magdelene] is awakened out of her loneliness by the sound of her own name spoken in a voice “so sweet the birds hush their singing.” It is beautiful to think of what the sounds of one’s own name would be, when the inflection of it would carry the meaning Mary heard in the unmistakable, familiar, and utterly unexpected voice of her friend and teacher. To propose analogies for the sound of it, a human name spoken in the world’s new morning, would seem to trivialize it. I admire the tact of the lyric in making no attempt to evoke it, except obliquely, in the hush that falls over the birds. But it is nonetheless at the center of the meaning of this story that we can know something of the inflection of that voice. Christ’s humanity is meant to speak to our humanity…The mystery of Christ’s humanity must make us wonder what mortal memory he carried beyond the grave, and whether his pleasure at the encounter with Mary would have been shadowed and enriched by the fact that, not so long before, he had had no friend to watch with him even one hour.

Our lives are shadowed and enriched by Mallonee’s voice and music, if we hear it. His work is a beacon in the desert night. He is waiting, watching with us–and that eases the waiting, the watching.

[1] A very simple example: the way food looks when we are hungry and not dieting, and the way it looks when we are not hungry and dieting.

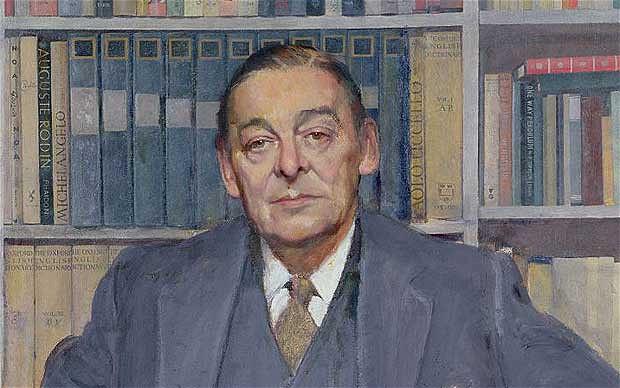

Philosopher (F. H. Bradley) (Poem)

I do realize that poetry–or an attempt at it–about obscure dead philosophers is not exactly a growth industry…

Philosopher (F. H. Bradley)

I do not know whether this in my case is a mark of senility, but I find myself now taking more and more as literal fact what I used in my youth to admire and love as poetry.” –Bradley

McTaggart, on meeting Bradley: “I felt as if a Platonic Idea had walked into the room.”

He lives

Stretched

Taut between

Appearance and reality

Overdone with

Metaphysics

Perhaps

Underdone with

Virtue

He does not much leave the house

As if drumly

Knowledge

Of the Good

Could substitute

For living

In its light

“On all questions, if you push me far enough, at present I end in doubts and perplexities.”

He lives

Systemless

Amid systems

Without a view

In an age

Of worldviews

“The older I grow, the more I recoil from any forced venture in the dark.”

Mortal

And so

Wounded

He picks

The scab

Nothing is

Removed from

Existence by

Being labelled

“Appearance”

He lives

Stuck

With it all

All is real

Even if not

Really real

His habitual mood

Diffident bewilderment–

It is all too

Too much

There is

No lorica

No padding

Against it all

Vulnerability

Is demanded

Bleeding

Is conclusive

Acknowledgement

Of the real

An opened

Wound

The sign

Of self-sacrifice

Increscunt animi, virescit volnere virtus

Philosophy demands

That he extinguish

Spiritual pride

But nothing

Kindles that fire

More

Vanity snuffs

Wisdom

So he must

Not think

He can save

Anyone else

The trouble

Of thinking

The goal

Is to stimulate

Thoughts on

First principles

And not

To supply them

The love

Of wisdom

Is love

Unsatisfied

In the twilight

He sounds out

The idols

He has ears even behind his ears

His truths

Are borne

In time

He lives

Stretched absolutely taut

Between dogmatism

And skepticism

Yes

And

No

John Herman Randall, Jr. on Bradley’s Book of Life

I compare reading JHR’s peculiar paper, “F. H. Bradley and the Working-Out of Absolute Idealism” (JHP Vol 5, No 3 July 1967) to trying to find a penny on the floor of a room in which the only light is a strobe light. Just when you start to see, everything goes black; and just when you give up on seeing, light flashes. Anyway, here is a memorable paragraph from the paper, one in which Randall is describing Bradley’s Appearance and Reality.

To use a metaphor, Bradley was trying to get the whole of life expressed in a book, to express all aspects of everything in words. A book about life never succeeds in doing that, it always falls short, it remains one-sided and incomplete. So Bradley was driven toward the perfect book–an Encyclopedia Britannica more glorious. But he tried to write it as James Joyce would have written it: He follows the method of Hegel’s Phenomenology. The book ought really to be a play, like Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude, where the characters express all their private feelings, in their contradictions, all at once. The perfect play would include and express everything. This effort would end in more than a book or even a play: It would be life itself. Bradley is trying to write the drama of life as it is, with all the stage directions, to express, not only what the actors do, say, think, and feel, but also what they are expressing. If one could succeed, the result would be life itself, completely known. We would see why, we would understand–and also we would feel the very tang of life itself!

Applause.

Remarkable. The metaphor and its deployment are inspired. There’s the happy linking of Joyce and Hegel, of Ulysses and the Phenomenology. There’s the reference to the O’Neill play; but also the charm of thinking of Bradley’s book as itself a Strange Interlude. There’s the joyous detail of taking Bradley to want to include even the stage directions. And there’s the tangy conclusion.

Here Randall sees deep into Appearance and Reality. The paragraph not only characterizes Bradley’s aim as a philosopher, but it suggests why poets of the caliber of Eliot and of Geoffrey Hill could take Bradley as (a) master: two poets who want us to see why, to understand, but also to feel the very tang of life itself. (It also suggests why it is that passages in Bradley seem often to echo Browning, to share in Browning’s gift for ventriloquy,: Bradley employs that gift masterfully in giving voice to the views caught up in his dialectic.)

Dorothy Parker, Coda (Poem)

There’s little in taking or giving,

There’s little in water or wine;

This living, this living, this living

Was never a project of mine.

Oh, hard is the struggle, and sparse is

The grain of the one at the top,

For art is a form of catharsis,

And love is a permanent flop,

And work is the province of cattle,

And rest’s for a clam in a shell,

So I’m thinking of throwing the battle–

Would you kindly direct me to hell?

Howard Nemerov on Paul Klee

For such a man, art is an act of faith:

Prayer the study of it, as Blake says,

And praise the practice; nor does he divide

Making from teaching, or from

theory. The three are one. . . .

RIP, T. S. Eliot

“For last year’s words belong to last year’s language

And next year’s words await another voice.

And to make an end is to make a beginning.”

‘Eat’, ‘Prey’, ‘Love’? (Poem)

‘Eat’, ‘Prey’, ‘Love’?

Abuzz

With words

Hived in paper

Droning on

Syrupping my mouth

Stickying my hands

Honeycombing my hair

Killer bees

Word sting

Aswarm

With words

Ankle high

Word pile

Kick the anthill

Words skitter scatter

Up pants leg

Tiny electroshocks

Fire ants

Word bite

Acrawl

With words

Words fight back

Mean me no good

Retreat

Hiphopping

Blowing smoke

But no control

They live

Hive- and hill-minded

One over many

Hear them talking

Amongst themselves

Barely audible hubbub

Me against babel

Queen bee

Queen ant:

Wannabe, can’t

No control

Orders ignored

Declining to decline

Buggy grammarian’s funeral

The words sing together

Die from the head down

Feet up

My corpse

Word food

Helen Vendler on Poetry and Paraphrase

As is often said, but as often forgotten, poems are not their paraphrases, because the paraphrase does not represent the thinking process as it strives toward ultimate precision, but rather reduces the poem to summarized “thoughts” or “statements” or “meanings”.